Impressions of Aruba's linguistic landscape

2022-03-23 21:06. Keywords: Linguistic Landscape, Aruba, Multilingualism, Language Attitudes

In February 2022, I had the wonderful opportunity to visit Aruba again. I spent a lot of time there as a kid and teenager, and I think the exposure to Aruba and Papiamento at a relatively early age is largely responsible for the path my career has taken. Although my previous visit to Aruba was in 2005 or 2006, before I started my master studies in linguistics, I did one of my senior projects (BA studies) on Papiamento and I’ve always wanted to get back to it somehow. I decided, inspired by Bamberger, Mijts, and Supheert (2016), to have a look at the linguistic landscape while on the island. This would be something I could do, I thought, while maintaining a laid-back, vacation-oriented demeanor.

The Bamberger, Mijts, and Supheert (2016) article looked at signage on a stretch of two streets — one “touristy” and one “non-touristy”, defined by public transportation routes — in three (peri-)urban centers on the island, Noord, Oranjestad, and San Nicolas. They were specifically interested in what the linguistic landscapes had to say about the increasing usage of English across domains in Aruban society, so understandably, they needed to to have a well delimited research area and rigorously created a corpus of all signs, 999 items in total, within the six areas. Since I neither wanted to simply recreate the work of Bamberger, Mijts, and Supheert nor get into such a rigorous data collection procedure (vacation mode), I needed to come up with something that would be more interesting from a qualitative perspective. I wondered what signage could tell us about the relative prestige of the four major languages spoken on Aruba and vitality of Papiamento. Additionally, in their analysis, Bamberg, Mijts and Supheert specifically excluded multilingual signs (2016: 55), but IMO these signs have a lot to say about language attitudes.

What information is conveyed in which languages? What information is “worth” translating into which languages? And what’s the status of writing in the two official languages — Dutch and Papiamento — in relation to English and Spanish which are also widely used on Aruba?

Background

Aruba is a small island of ca. 180km2, which lies in the Caribbean sea just 29km north of the Venezuelan Paraguaná peninsula. Amerindian peoples related to those of coastal Venezuela and Colombia occupied Aruba, as well as Curaçao and Bonaire, long before the arrival of Europeans. But the Spanish claimed Aruba in 1499 and from the early 16th the Amerindian populations were decimated via enslavement and deportation. Aside from human resources, Spain did not find much use in the dry, rocky island, so Aruba was mostly neglected until the Dutch took over administration of the ABC islands in 1634. The few Amerindians who survived the Spanish period (or were returned or migrated from the mainland) were allowed to remain on Aruba, tasked with grazing livestock for the colonial enterprise to be used / sold for meat in other parts of the region.

Establishment of Papiamento

...meanwhile in Curaçao — Not long after the Dutch annexed the ABC islands,1 the West India Company (WIC), which was in charge of Dutch colonial ventures, instigated a large transfer of slaves to the new world; a transshipment depot was established on Curaçao facilitated by its excellent harbor and proximity to a variety of markets (Jacobs 2012: 289–291). Thanks to an ongoing conflict between Spain and Portugal, the WIC was able to establish itself as important middle-men in the trade, providing large numbers of slaves, sourced in Portuguese West Africa to Spanish New world (Jacobs 2012: 291–294). Although most slaves stayed in Curaçao only for a short time, those from Upper Guinea Coast with knowledge of UG Portuguese Creole were preferred candidates for staying on the island (Jacobs 2012: 308–319). The Dutch settlers on the island by and large excluded the the slave populations from learning and using the Dutch language; they preferred emergent Papiamento as a lingua franca for communication outside their elite circles. This implicit language policy in 17th and 18th centuries effectively allowed for Papiamento to develop freely and become firmly established on the island, but at the same time created linguistically oriented social stratification that provides some of the basis for modern language ideologies whereby Papiamento is perceived as second-rate in comparison to European languages (Pereira 2018: 24–25). Due to economic, religious and personal contacts, a relexification of much of UG Portuguese Creole’s basic vocabulary occurred, replacing the most common lexical items with Spanish-like equivalents while leaving the bulk of grammatical structures in parallel to Upper Guinea Portuguese Creole (Jacobs 2012: 319–335). Aruba was only opened for settlement sometime in the second half of the 18th century, after which the bulk of settlers came directly from Curaçao, bringing Papiamento with them along with a general aversion to the use of Dutch in domains of everyday life (Pereira 2018: 27).

Papiamento in context

The Dutch civilizing mission came late (relative to other European colonizers). In the early 19th century, the kingdom of the Netherlands initiated policies to unify the European Netherlands with the islands and other territories in matters of law, culture and language — what they perceived to be the civilized world (Pereira 2018: 27–30). From 1819, an explicit policy of Dutch-language education was instituted, and implemented in 1822 on Aruba with the appointment of a schoolmaster (Mijts 2021: 132–133). Dutch remained the language of education and the legal system on Aruba through the end of formal colonization with creation of Netherlands Antilles in 1954, Aruba’s separation from the Netherlands Antilles in 1986, and until today, despite the fact that a small minority of residents (c.a. 6% as of 2010) claim Dutch as their household language in recent census data and the fact that Language Policy and Planning is a country-level legal issue (i.e. it is not compelled by constituency in the Kingdom of the Netherlands) (Mijts 2021: 134–136).

The economies of the ABC islands were troubled following the abolition of slavery in the 1863, but a solution came with the discovery of oil deposits in nearby Venezuela. Starting in the 1920s, a crude oil transshipment facility and refinery facilities were established on Aruba, which triggered an influx of migrant workers speaking Caribbean and American varieties of English (Pereira 2018: 45, 75; Mijts 2021: 35). The large Lago facility was closed in 1985, just before the succession of Aruba from the Netherlands Antilles, and the Aruban government took the decision to focus on developing the tourism sector, catering primarily to American tourists. Today English is the main language of 7% of households in Aruba, but despite the relatively low numbers of reported use in the household, English hold a fairly prestigious position as the language of local and international commerce and international education.

Spanish also plays a significant role on the island due to cultural, commercial, family, religious ties, and oil industry related migration. Spanish is the second most spoken language on Aruba, with 14% of households. Papiamento is undoubtedly the most spoken language on the island; it has a relatively high prestige compared to other creole languages in post-colonial settings and although it was legally recognized as an official language in 2003, “in practice there is only weak, inconsistent support” (Mijts 2021: 99). Particularly due to the history of language policies on the island, and in combination with the more recent oil and tourism industry, the position of Papiamento is delicate, despite its numerical dominance. Even a quick jaunt any place on the island reveals that signs are mostly not in the either of the two official languages. Let’s take a closer look to see if a small corpus of signs reveals anything interesting about attitudes toward these four main languages.

Collecting Data

The data collection procedures were very simple. Wherever I went, I took pictures of as many signs as I could. I followed this opportunistic approach mainly because I was on vacation and didn’t want to drag my family around to strange places or miss out on swimming or other touristy stuff because I had to get out and take pictures. I ignored street signs (that is the names of streets) because there is a database of street names in Aruba (more on this later). I can also admit, that I didn’t take pictures of every sign I saw — in some areas (especially touristy areas) one is inundated with signs, mostly in English and / or Spanish about products and services for sale. On other occasions, I was driving or riding in a car and interesting signs went by too quickly to get a picture. Although this a-systematicity means that the conclusions to be drawn are somewhat limited,2 there are some interesting qualitative observations to be made from these images.

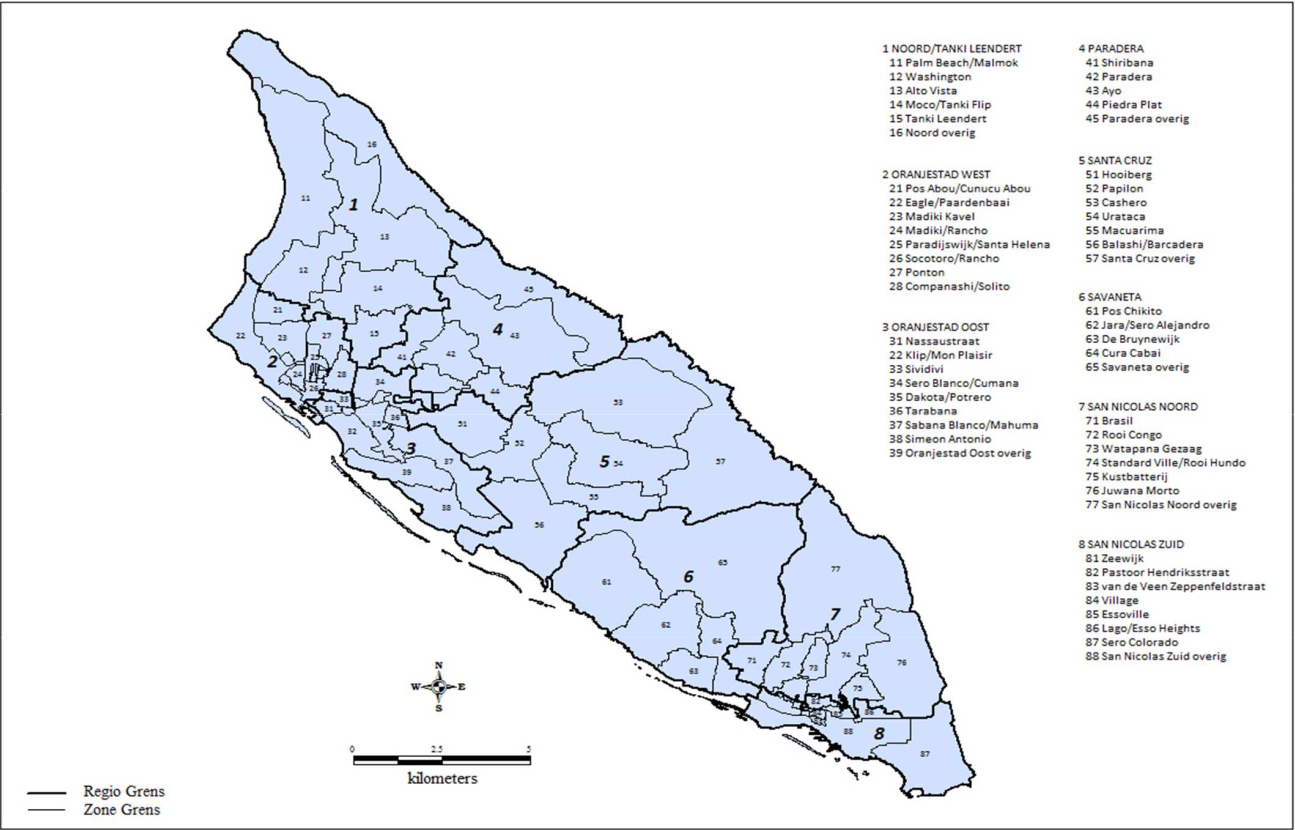

All in all I collected pictures of 296 unique signs pictures from around the island. The particular areas where signs were photographed were skewed, of course, toward the parts of the island where I spend most time — Oranjestad West and Oranjestad Oost. Table 1 provides a breakdown of number of pictures per region and Figure 1 shows the administrative regions and zones on the island.

| Region | Region code | N signs |

| Oranjestad West | 2 | 170 |

| Oranjestad Oost | 3 | 87 |

| San Nicolas Noord | 7 | 15 |

| Noord/Tanki Leendert | 1 | 14 |

| Santa Cruz | 5 | 6 |

| Paradera | 4 | 3 |

| San Nicolas Zuid | 8 | 1 |

Table 1: Number of signs photographed per region.

Figure 1: Aruba’s regions and zones (Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek 2014).

Analyzing Data

What is a sign?

I already indicated how many signs I photographed, and while the definition of a “sign” is rather intuitive, it is worth explicating exactly what I mean since I want to clearly differentiate instances multilingual signs from multiple instances of monolingual signs in different language. Here, a “sign” refers to a medium, or collection of media, that contains written language (not considering pictograms or other signs without written language). Additionally, to be considered here, a sign must have an identifiable language; some graffiti for instance contains ambiguous words or initials, which is then not part of the analysis. A collection of such media is considered a single sign when it has:

- single (institutional) author

- shared motif

- single thematic message

- proximity (can be easily read from one place)

Figure 2: What counts as a sign?

2a. Contains three signs, with different authors and motifs.

2b. Only one sign.

Monolingual Signs

Most signs were monolingual (n=222, 75%). I categorized the monolingual signs according to the same criteria as Bamberger, Mijts, and Supheert (2016: 54). The results of this are presented in Table 2.

| Domain | Dutch | English | Papiamento | Spanish | Total |

| Cultural | 3 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 11 |

| Educational | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Governmental | 8 | 7 | 9 | 0 | 24 |

| Top Down subt. | 11 | 11 | 13 | 1 | 36 |

| Religious | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| Commercial | 3 | 48 | 5 | 4 | 60 |

| Private | 6 | 82 | 23 | 9 | 120 |

| Bottom up subt. | 9 | 131 | 30 | 15 | 185 |

| Total | 20 | 142 | 43 | 16 | 221 |

Table 2: Monolingual signs by domain and language.

Like Bamberger, Mijts, and Supheert (2016), the vast majority (approx. 64%) of monolingual signs are in English. Also similar is that English and Papiamento signs are found in all domains,3 while Spanish is limited to bottom-up domains and Dutch is prominent in top-down domains.4 About 87% of the images I collected are from Oranjestad (Oost and West), so a comparison of all regions isn’t sensible, but a comparison of the two Oranjestad regions is presented in Table 3.

| Oranjestad Oost | Oranjestad West | |||||||

| Du | En | Pa | Sp | Du | En | Pa | Sp | |

| TD | 7 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| BU | 5 | 27 | 16 | 5 | 4 | 90 | 12 | 8 |

Table 3: Number of monolingual signs by language in Oranjestad Oost and Oranjestad West. Rows are aggregated by top-down (TD) and bottom-up (BU) domains.

Similar to the overall collection of images, the majority of signage is monolingual (OO=68%, OW=79%) in both areas. There is a noticeably higher proportion of English signs in bottom-up domains in Oranjestad West, but a ranking of signs by language in both areas is consistent with the overall collection of monolingual signs. The higher percentage of English signs in Oranjestad West is potentially understood as an effect of the fact that the main hotel area begins in Oranjestad West, and is concentrated primarily on the northwestern coast of the island. However not all monolingual signs in English in OW appear to be targeting tourists. Figure 3 illustrates this, depicting monolingual English signs in decidedly non-touristy contexts (construction and commercial real estate), calling for a more nuanced explanation of English signage.

Figure 3: Monolingual English Signs not apparently targeting tourists, away from the hotel area in Oranjestad West.

3a. English on the job.

3b. Rent a business.

Generally speaking, in comparison with Bamberger, Mijts, and Supheert’s findings (2016), the monolingual signs in the current data set lead to similar conclusions. Dutch signs are primarily top-down, governmental signs. Papiamento signage is found in all domains, though less so than English. Spanish signs are relatively few and limited to bottom-up domains.

Multilingual Signs

Considering all signs in the corpus, the data suggest that there is a preference for fewer languages on a sign. A breakdown of signs by number of languages is in Table 4.

| N | |

| One language | 222 |

| Two languages | 54 |

| Three languages | 12 |

| Four languages | 8 |

Table 4: Signs by number of languages. N.b. There’s an additional monolingual sign not accounted for in Table 2 because it’s in Sranantongo! See Figure 16a

Bilingual signs account for about 18% of the data set. All combinations of the four main languages under consideration are found with the exception of Dutch-Spanish. Only a single sign was found to have Papaimento and Spanish, which was a private warning in the Lourdes shrine about not burning candles on the flammable baby Jesus display (see Figure 12a). Next, a handful of signs in Dutch and English; three were commercial signs and one a Governmental road sign. With Dutch and Papiamento as official languages, one might expect a large number of bilingual signs in these languages on Aruba, but there were just seven across several domains – governmental, private, and religious.

| Languages (aggregated alphabetical) | language combination | N | Total |

| Du-En | 4 | ||

| Du-En | 2 | ||

| En-Du | 2 | ||

| Du-Pa | 7 | ||

| Du-Pa | 5 | ||

| Pa-Du | 2 | ||

| En-Pa | 21 | ||

| En-Pa | 8 | ||

| Pa-En | 13 | ||

| En-Sp | 18 | ||

| En-Sp | 18 | ||

| Pa-Sp | 1 | ||

| Sp-Pa | 1 |

Table 5: Bilingual signs in the landscape. N.b. the total number of signs in the table is 3 short of the Bilingual signs indicated in Table because there were two instances where one language couldn’t be clearly identified and another instance of a sign in English and Cebuano (an advert for a Filipino restaurant, Figure 16b.

Next, there are 18 signs with Spanish and English; these are Private Warnings, Governmental Warnings, or Cultural Monuments, all targeting tourists. Finally, the largest number of bilingual signs are written in English and Papiamento, and cut across all domains.

Like monolingual signage, English is dominant in bilingual signs, appearing on some 80% of bilingual signs in the set. The distribution languages in bilingual signs is similar overall to that of monolingual signs, shown in Table 6, with the exception that Spanish occurs nearly twice as often as Dutch.

| Dutch | 11 | 20% |

| English | 43 | 80% |

| Papiamento | 29 | 54% |

| Spanish | 19 | 35% |

Table 6: Distribution of languages on 54 bilingual signs.

The order that languages appear on multilingual signs is also potentially of interest to understanding language attitudes on Aruba. Throughout this work (and others), the dominance of English in the linguistic landscape has been emphasized, but interestingly on bilingual signs English only dominantly appears first in relation to Spanish. On Dutch-English bilingual signs the two languages appear first equally as often,5 and Papiamento appears first more often on English-Papiamento bilingual signs. So on the one hand, we have a clear message about the relative prestige of English and Spanish, but a less clear message about the relation ship between English and Dutch or Papiamento on the other. Another prevalent theme in the literature regarding language attitudes on Aruba is Papiamento’s apparent inferiority complex (see e.g. Pereira 2018; Mijts 2021), so it’s encouraging to see the language more often preceding English, and sometimes preceding Dutch, even on top-down messages.

There were 12 signs written in three languages. Trilingual signs are almost exclusively Privates signs (one Cultural monument, and one Commercial sign); these are detailed in Table 7.

| Languages (aggregated alphabetical) | language combination | N | Total |

| Du-En-Pa | 9 | ||

| Du-Pa-En | 2 | ||

| En-Du-Pa | 1 | ||

| En-Pa-Du | 3 | ||

| Pa-En-Du | 3 | ||

| En-Pa-Sp | 3 | ||

| En-Pa-Sp | 1 | ||

| Pa-En-Sp | 2 |

Table 7: Trilingual signs in the landscape.

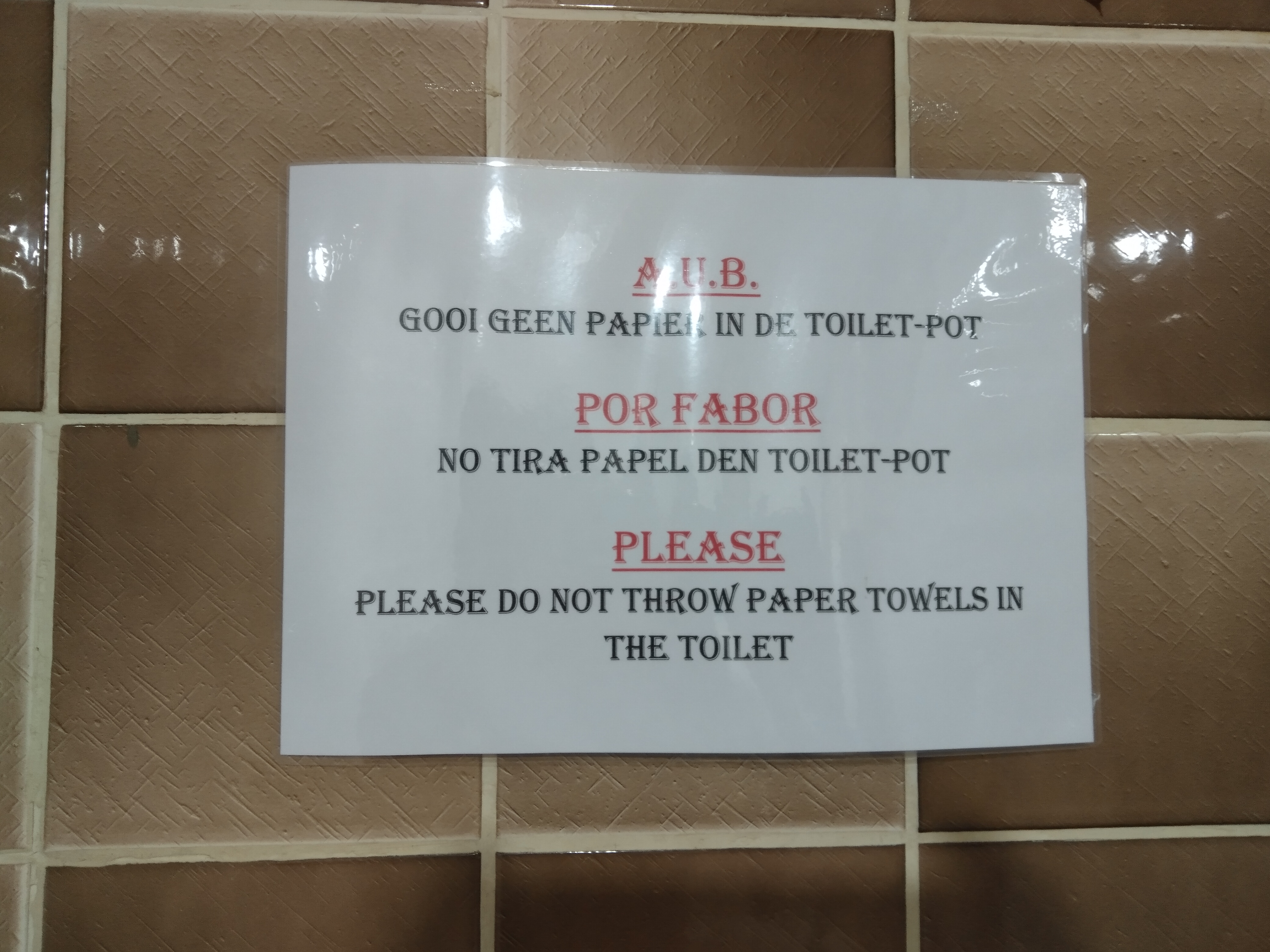

English and Papiamento both appear in all trilingual signs. The fact that Spanish either comes in third or is left off all together is, once again, potentially indicative of its relative level of prestige on the island. Similarly, and curiously, Dutch appears in just three trilingual signs (Figure 4), perhaps speaking to its perceived utility on the island.

Figure 4: Trilingual signs containing Dutch.

4a. A toilet in Noord.

4b. South entrance of Arikok National Park (military warning to the right).

4c. A storefront in Oranjestad (look at the health warning on the cigarette advert).

The remaining 8 multilingual signs are written in all four of Aruba’s major languages. As shown in Table 8, the quadrilingual signage displays a variety of ordering of languages.

| Languages | N |

| En-Du-Pa-Sp | 2 |

| En-Du-Sp-Pa | 1 |

| En-Pa-Sp-Du | 1 |

| En-Sp-Pa-Du | 1 |

| Pa-En-Du-Sp | 2 |

| Pa-En-Sp-Du | 1 |

Table 8: Ordering of languages in quadrilingual signs.

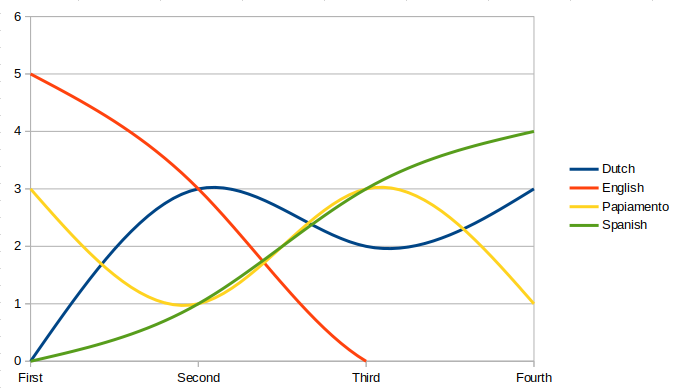

Nevertheless, the trends from previously described signage are evident — English and Papiamento are most often shown first while Dutch and Spanish are most often later. But this is a trend (based on a very small sample) rather than a rule. Despite the fact that there are just eight quadrilingual signs in the sample, it seems to me that visualizing the frequencies of each language’s position in the order is telling in regards to attitudes about the relative status of Aruba’s major languages. In Figure 5, the number of occurrences of a language in a given position — first through fourth — is plotted on a line. If order of languages on a sign is at all indicative of attitudes about relative statuses, we may extrapolate that downward sloping lines represent languages with high prestige and conversely that upward sloping lines represent languages with low prestige. The wavy curvature of the lines for Dutch and Papiamento speak to their more nuanced position in society.

Figure 5: Position of languages relative to the 3 other major languages of Aruba.

Codemixing?

The written word is not typically the first-stop when looking for a domain where one would expect to find a lot of code mixing. And indeed, the vast majority of the multilingual signs collected here clearly delimit languages. There are some minor exceptions, such as single words or short phrases that are cognate in Papiamento and Spanish – these cases were mentioned already in the caption of Table 5. Another exception is the Private Warning sign outside the now-closed bar at Boca Prins in (1).

(1) No mag trese bo mesun cuminda.

'You may not bring your own food or drink.' (Figure 6a)

The modal mag, clearly of Dutch origin, isn’t usually described as belonging to the Tense-Mood-Aspect system of Papiamento (see e.g. Goilo 1962; Kouwenberg and Murray 1994). Perhaps there is no permission category in the system (NaN but I don’t think you could substitute por without changing the meaning), thus the borrowing a borrowing was instantiated by a multilingual who “needed” that category. It was exciting for me because the same phenomenon is found among Sranan speakers in Suriname. I’ll never forget the example from the show Politie Paramaribo (a Cops-like show filmed in Paramaribo), which I think I watched before my first fieldwork in Suriname, where the police had to inform a driver with an expired license Yu no mag rij moro‘You may not drive anymore.’

Here are a several more examples in (2), all taken from a single store front on Main st. in Oranjestad. These examples seem to echo very well the amount and type of codemixing that one regularly encounters with spoken, informal Papiamento.

(2) More examples from signs with code mixing. (Figure 8b)

a. Please hasi uso di hand sanitizer poni ora di drenta.

‘Please use hand sanitizer before you enter.’

b. Please sanitize bo mannan ora di drenta y sali.

‘Please sanitize your hands when you enter and leave’

c. Please corda mantene social distance.

‘Please remember to maintain social distance.’

d. Handschoen no ta permiti.

‘Gloves are not allowed.’

e. Bo persona mester tin un mondkapje bisti pa drenta.

‘You must wear a mask to enter.’

Another honorable mention here in the codeswitching section is this bumper sticker I saw in Oranjestad (not included as a ‘sign’ in the data set) — Figure 6b, which reads tur freaking dia ‘every freaking day’ — how about that? Different languages right across the phrase boundary. These are fun examples, but unfortunately very much in the minority.

Figure 6: Code mixing in written media.

6a. Bar in Boca Prins.

6b. Sticker on a parked car in Oranjestad.

Street names

Street names are an important component of linguistic landscape. As I mentioned above, I didn’t include street signs in the small corpus described in the previous sections. This is because there is an extensive list of street names that can be analyzed in it’s entirety. The obvious benefit to this strategy is that one can examine all the street names on the island. The downside, however, is that analyzing street names from a list doesn’t tell us anything about the real salience of the name in the landscape — Is there even a sign with a street’s name? Is the street small with a few houses in a rural area, or is it a long street in an urban area with many signs indicating the street name and businesses advertising along with their address? In the spirit of less-than-rigorous, vacation mode, let’s have a look at the list.

First, I extracted all the 895 street names and numerical street codes from the Geografische Adressen Classificatie Aruba (Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek 2014) and made an attempt at automating classifying street names by language with a Python script. A street name is considered Dutch if it ends with:

- batterij

- laan

- plein

- straat

- weg

- wijk

- noord

- oost

- zuid

- beach

- complex

- island

- cas

- caya

- pos

- rooi

- sero

A street name is considered Spanish if it contains:

- ñ

- santa

Unambiguous classification of a street name was not exclusive, which also allows for an examination of potentially multilingual street names. This relatively simple method identified the language of 707 street names. I then took a look at the list to manually confirm the classifications and identify some additional entries, bringing the total of classified street names to 769 (126 still unclassified). This could be looked at in more detail, but I just don’t know enough Papaimento to know whether or not names like Camacuri, Malmok, or Sividivi are Papiamento or not.

| N | |

| Monolingual Street Names | 731 |

| Multilingual Street Names | 21 |

Table 9: Monolingual vs multilingual street names

Like the corpus of photographed signage, one language is the norm for street names (Table 9). Table 10 provides a breakdown of the street names by language. Note that the total isn’t equal to the total of classified street names because of the multilingual and ambiguous entries. Contrary to the corpus of signs discussed previously, the majority of street names are Dutch, followed by Papiamento, then Spanish. English is used in the fewest number of street names.

| N | |

| Dutch | 561 |

| English | 26 |

| Papiamento | 189 |

| Spanish | 35 |

Table 10: Number of street names in a given language

The few examples of multilingual street names can be grouped into two categories, those that are listed with translations of a single name in (3), and those that have components from multiple languages in a single name (4).

(3) Street addresses with multiple language versions (N = 3)

a. Free zone / Vrije zone

b. Oranjestad Port / Haven Oranjestad

c. Kinikinistraat / Caya Kinikini

(4) Single street addresses with components from multiple languages

a. Weg Sero Blanco

b. Pos Chikito Complex

c. Rooiweg

d. Sero Dos Posweg

The fact that Dutch occupies the first place in the ranking of street names by language is undoubtedly a vestige of Aruba’s colonial history. Like the corpus of signs, Papiamento occupies a solid second place in the ranking. English, despite its widespread usage in signage as well as spoken form, in the last place suggests something about its position on the island; while tolerated and even necessary for economic purposes on the Island, it too is seen as a guest that isn’t really fundamental to the local identity.

The last page of Geografische Adressen Classificatie Aruba lists additions and changes to street and neighborhood names between 2005 and its publication in 2005 (Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek 2014: 82). The two changes indicated are a renaming of Dutch-named streets to Papiamento ones and none of the additions are Dutch names, perhaps indicating a further obsoleting of Dutch in Aruban society. (It would be interesting to order street names by year of their naming to check this hypothesis, but I don’t have access to that information right now.) Most of the added street / neighborhood names are clear Papiamento, but a further interesting observation is that some of them are also Spanish. The corpus of signs (as well as Bamberger, Mijts, and Supheert 2016: 62) suggest a fairly low overall prestige for Spanish on the island, but new street names in Spanish, we must then consider the position of Spanish to be rather more nuanced.

Discussion

Aside from enjoying my vacation, I set out on Aruba to try to better understand language attitudes and vitality of Papiamento through public written media — signs. It was easy enough to collect a bunch of data while keeping cool (so to speak) and relaxed, and after taking a careful look at all the signs I photographed, some interesting observations emerge. There is a fascinating multilingual setting on Aruba. Touristy-type material often boasts that “almost everyone on Aruba speaks four languages”, which is probably true, but the situation is more complex — not all languages are created equal in the Aruban context.

Like the Bamberger, Mijts, and Supheert (2016) article, the data presented here confirm the overwhelming dominance of English in the linguistic landscape. To some extent, this has to do with tourism, but I wonder, to what extent the dominance is indicative of high prestige of English. How much does economy and communicative efficiency have to do with English dominance when probably the majority, if not all, residents of Aruba as well as Dutch tourists are perfectly capable of understanding Dutch signage? What’s the price difference of importing generic signs like construction safety and real estate (Figure 3) as opposed to producing them locally? What kind of English “legacy” was already in place on the island from the oil industry before the tourism boom of the 1980’s?

Utility and economics might play some role in English dominance in monolingual signage, and to some extent in bilingual signage (Does the high proportion of English-Spanish bilingual signs mean that Spanish-speaking tourists aren’t expected to know English?), but the ordering of languages on multilingual signs seems to speak volumes about languages’ prestige on Aruba. Indeed English is most often first and Spanish is last. Meanwhile the two actual official languages of struggle for position in the middle.

The apparent low prestige of Spanish has been mentioned several times here, and indeed the lack of signs in top-down domains, or the fact that it’s never first and most likely to be left off a multilingual sign is indicative of that. However the appearance of new Spanish street names suggests there’s more to the story — is there some older sense of, perhaps covert, prestige, maybe due to the use of Spanish in religion dating back to the earliest priests proselytizing on Aruba?

Dutch signs, too, are relatively few overall, and Dutch is also likely to be left off a multilingual sign. Perhaps this has to do with its perceived utility. As Mijts (2021) demonstrates, language ideologies that developed under the colonial period, whereby Dutch (or generally European languages) are somehow inherently superior to a creole language like Papiamento, are still active in the minds of many people on Aruba. This struggle between Aruba’s two official languages is ever so evident on multilingual signs, where the order between Papiamento and Dutch is not predictable. Also telling that no new streets were given Dutch names, nor were any streets renamed to Dutch names. I hope it signifies the Aruban people continue to shake off the hundreds of years of stigma ascribed to Papiamento!

My stay on Aruba coincided with the UNESCO Declared International Mother Tongue Day (February 21). Several local newspapers ran stories about this the following day, calling for the additional development and protection of Papiamento, as well as expansion of domains where it is / can be used — Headline: Papiamento mester di mas defensa! “Papiamento must be protected!” (Diario). It was also announced that a National Institute of Linguistics is to be instated over the coming three months to do just that, Pronto Aruba lo haya un instituto linguistico nacional “Soon Aruba will get a National Institute of linguistics” (Solo). Judging from observations in the local media (TV, radio and newspaper) as well as conversations with people who live on Aruba, this seems rather necessary as English, Spanish, and Dutch terms are regularly inserted to Papiamento, so much so that (at least according to several people I spoke with) young people can hardly speak in complete Papiamento sentences.6 “They just prefer to speak English, even amongst themselves.” Perhaps if the authorities could agree on a stable mother-tongue pedagogical plan for students on the island, the intensive multilingual context would be less of a threat to Papiamento’s vitality.

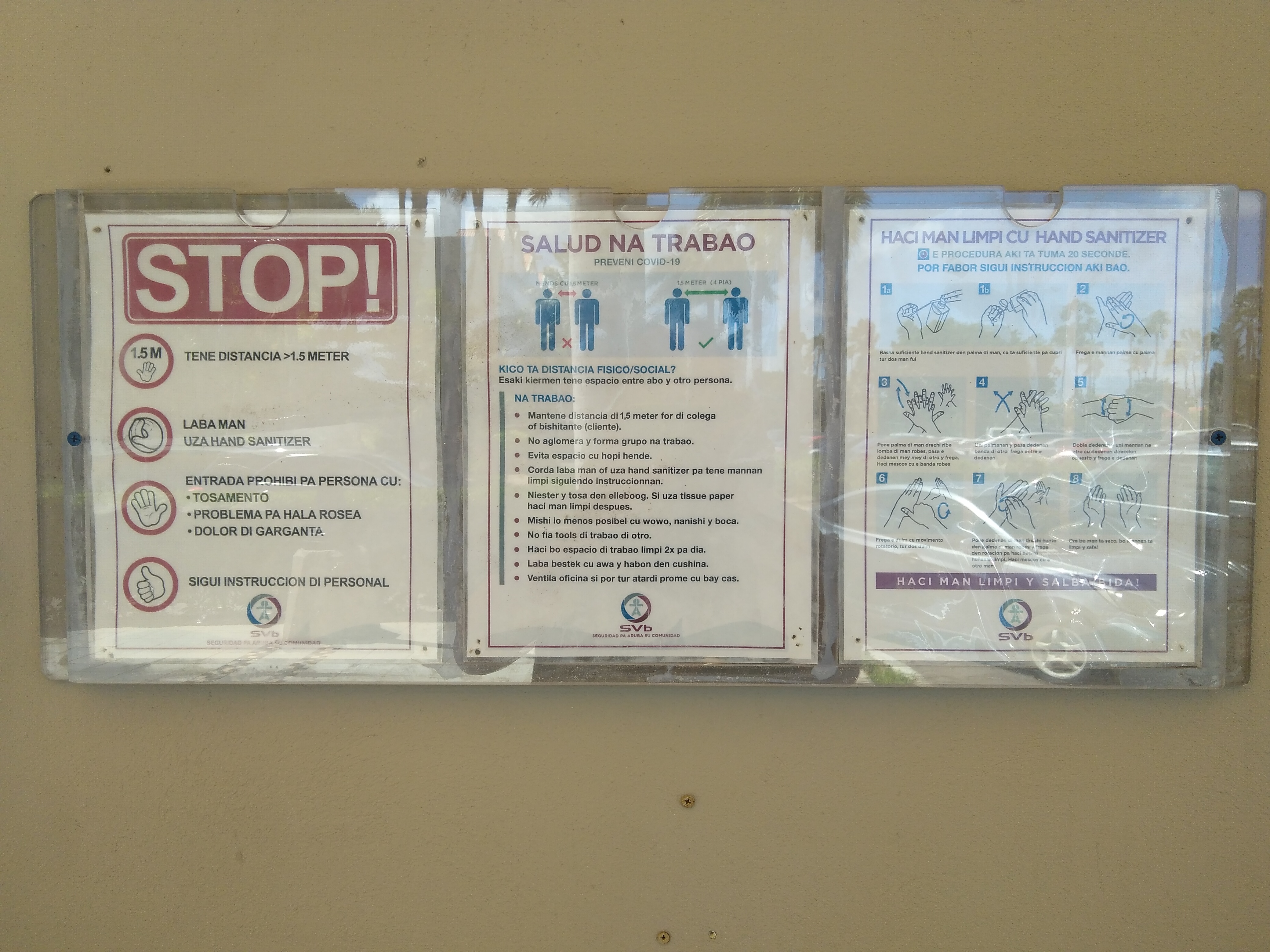

In terms of Papiamento in the linguistic landscape, by all measures, it has a solid second place. Papiamento was found to be the second most used language on monolingual and multilingual signs, it’s featured across all domains, and it’s left-trending in the order of multilingual signs. Bamberger, Mijts, and Supheert wrote that there were few overall signs in the medical domain, with only one “...instance of medical signage in Papiamento [...] found in Noord’s non-touristic zone” (2016: 59). Having been “lucky enough” to visit in (what I hope is the end of) the COVID-19 era, there were plenty of instances of medical signage (see Figures 8 and 9). I also noted the addition of Papiamento street names, and the renaming of two previously Dutch-named streets to Papiamento. Without longitudinal or diachronic data, I can only home these represent an expansion of domains, however minor, and Papiamento will continue to be spoken well into the future.

Notes

1. That is, Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao. Go back to the text.

2. I do say “impressions” right in the title. Go back to the text.

3. Except Educational signs, which are underrepresented overall. Go back to the text.

4. It should be noted that although I have a higher relative frequency of Dutch items in bottom-up domains, the overall number of items (n=20) is fairly low and I used a less-rigorous data-collection technique, meaning my numbers may be due to unconscious bias or chance. Go back to the text.

5. Though 4 signs hardly seems comprehensive. Go back to the text.

6. Don’t get me wrong, I love a bit of good code mixing, but not when it comes at the expense of the vitality of one of the languages involved. Go back to the text.

References

Bamberger, Fardau, Eric Mijts, and Roselinde Supheert. 2016. “The languages in Aruba’s linguistic landscape: the representation of Aruba’s four dominant languages in written form in the public sphere”. In Embracing multiple identities : opting out of neocolonial monolingualism, monoculturalism and mono-identification in the Dutch Caribbean, 47–65. Islands in Between.

Jacobs, Bart. 2012. Origins of a Creole: The History of Papiamentu and Its African Ties. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

Pereira, J.L. 2018. Valorization of Papiamento: In Aruban Society and Education, in Historical, Contemporary and Future Perspectives. UCRI publication. University of Curaçao, Research Institute (UCRI).

Mijts, Eric. 2021. The situated construction of language ideologies in Aruba: a study among participants in the language planning and policy process. PhD thesis, University of Antwerp.

Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. 2014. GAC – Geografische Adressen Classificatie Aruba. Oranjestad, Aruba.

Goilo, E.R. 1962. Papiamentu Textbook. Oranjestad: De Wit N.V.

Kouwenberg, S., and E. Murray. 1994. Papiamentu: Languages of the world Materials. Munich: Lincom Europa.

Supplementary Images

And here come some more images of signs, because why not?

Figure 7: Papiamento first!

7a. Put your garbage where it belongs.

7b.Parking at the hospital.

Figure 8: Medical signage in Papiamento.

8a. Cas di Dokter.

8b. Some more codemixing, from a storefront on one of the main shopping streets in Oranjestad.

Figure 9: More COVID-19 stuff in Papiamento.

Figure 10: No Dutch on the signs at the Dutch supermarket.

Figure 11: Huge bilingual banner in Oranjestad West.

11a. Dutch side.

11b. Papiamento side.

Figure 12: No No NO.

12a. Don’t burn the baby Jesus.

12b. No Smoking.

Figure 13: House of Culture.

Figure 14: No Parking!

14a. Geen Parkering

14b. Only for Customers.

Figure 15: Misc. road signs.

15a. Busses only.

15b. Watch out for the speed bump.

Figure 16: Signs in languages other than Aruba’s four major languages.

16a. Sign in Sranantongto!

16b. Sign with some Cebuano words.

Figure 17: Prohibited!

17a. Private Terrain.

17b. No Swimming.

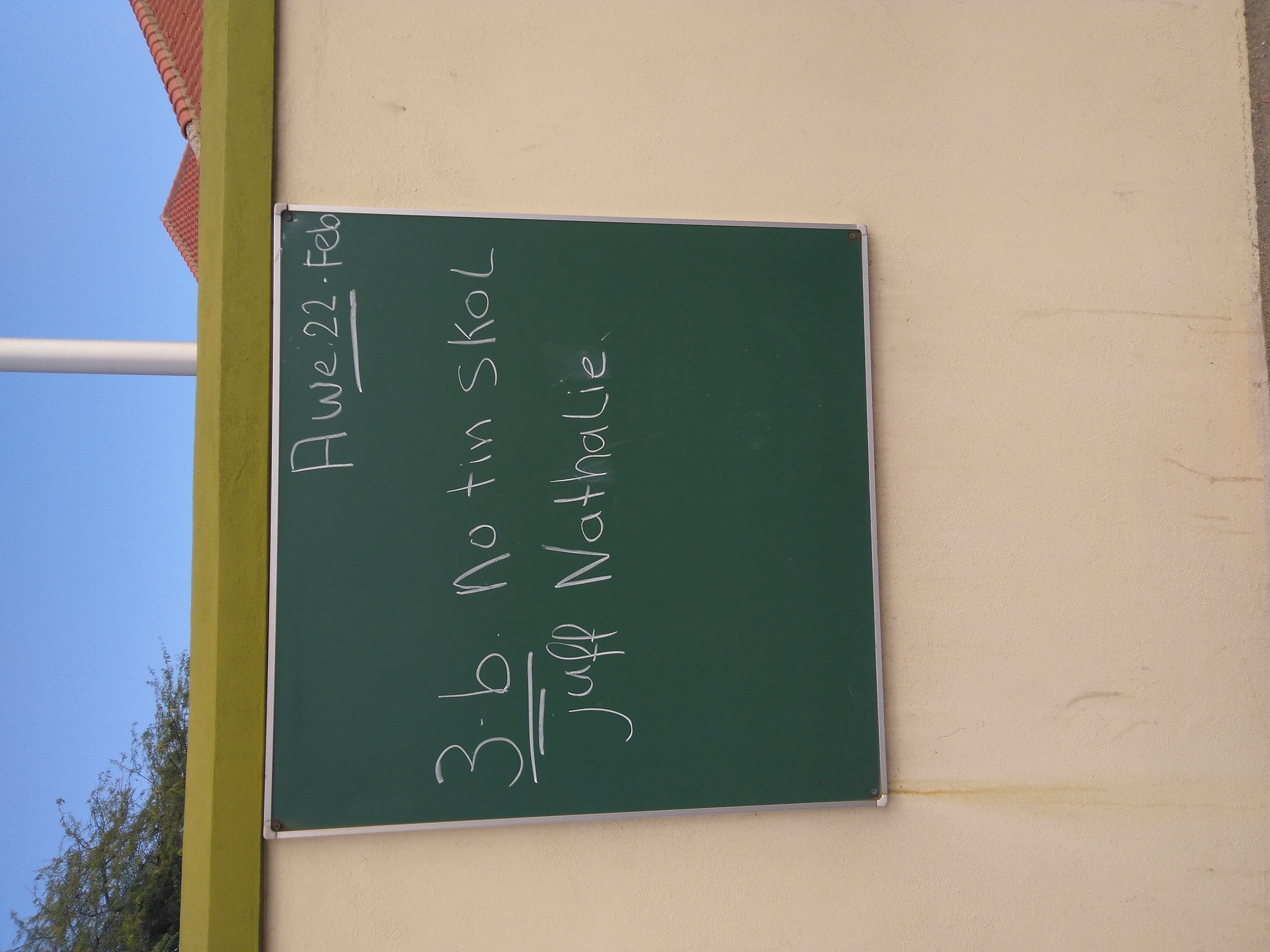

Figure 18: No School Today. Go study Papiamento.

Enter your name | alias and email to comment on this post.